A brief introduction to Aristotle’s virtue ethics

Virtue theory proclaims that people ought to incorporate certain virtues, defined as excellent traits, as part of their characters by habituating themselves to the practice of such traits as honesty and courage, etc. The opposite of virtue is vice.

Proponents of the theory, including the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC), suggest that, ideally, we need to do what is virtuous, and refrain from acting viciously. The assumption is that cultivating a good character is conducive to a society that functions in an orderly, harmonious, and cohesive manner. This is made possible insofar as a community acts virtuously with a view towards achieving the greater ‘common’ good.

What does all that mean? Why is it important to try and think about virtues to pursue individually and collectively? Are those universal? How do we decide which traits to cultivate?

Finding a definitive answer to these questions is almost an impossible task. In this article, I’m going to focus on the Aristotelian account.

For Aristotle, the good of the city is more important than the good of the individual. He argues that political leaders should be tasked with finding a suitable set of virtues that a community ought to revere and practice. Given their role as governors, politicians should work for the greater good; this includes deciding on and promoting certain virtues that would contribute to that end.

Of course, this might be counterintuitive nowadays because, in many instances, politicians to large extent end up doing what is in their best interest. This was not always the case in ancient Greece.

It is important to keep in mind that Aristotle isn’t interested in deriving, defining, or determining virtues and vices. Rather, he’s going to base his arguments on cardinal virtues (wisdom, courage, temperance, and justice) that were commonly accepted by the ancient Greeks, and will proceed to explain how we can acquire them.

It is most likely that the surviving Aristotle writings are lecture notes intended for his students at the Lyceum, which was the name of the academy he founded.

Aristotle sets out to develop his ethical framework in a treatise called Nicomachean Ethics (probably named after his son Nichomacus who edited it), showing how members of a society can live a good and practical life.

Happiness, the Chief Good, and Excellence

In the following passages, I will explain the concept of Eudaimonia, which roughly translates to happiness, flourishing, and contentment. Then I’ll turn to an examination of Arete (virtue and excellence), as well as the character traits that would make this possible.

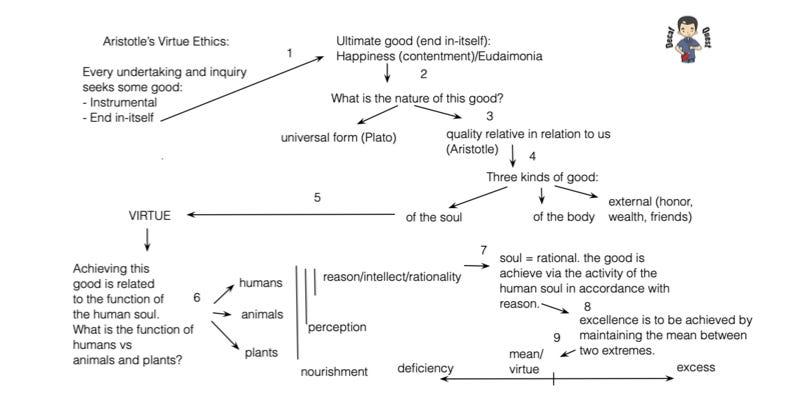

The first question Aristotle is going to be asking is as follows: what do human beings seek in life? Every action or inquiry that we undertake seems to be seeking some sort of good, it being either means to an end or an end in itself. We seek instrumental goods as means to an end because what we ultimately care for is the chief good, which is happiness.

E.g.: we seek education to find a job to make a living to live decently … to be happy.

What does it mean to be happy? Aristotle explains that there are different conceptions of it. Some people associate it with honor, others with pleasure, and some with wealth. Some even attempt to define it abstractly and end up associating it with the intellect.

Aristotle considers material ‘possessions’ a possible source of happiness but argues that because of their ephemeral nature, we can’t depend on them to reach a state of contentment and tranquility. It is essential, as a result, to examine human nature in more depth to find out which ‘good’ could potentially be the source of long-lasting ‘Eudaimonia’. This chief good, as Aristotle calls it, can be pursued (and perhaps acquired) by living in accordance with what distinguishes us, as humans, from other species: reason. Here’s how Aristotle defends his stance.

In order to determine the definition of the good, we need to figure out the function of the subject in question. A doctor’s function is to heal/treat people; a carpenter’s is to build good furniture; running shoes, to be durable, etc. A good doctor, therefore, is someone who fulfills her function.

In a counterargument to Plato’s theory of forms, Aristotle asserts that there is no universal definition of a substance of goodness (in the sense of Plato), there are different qualities of the good, relative in relation to us. Good doctor vs good carpenter vs good athlete vs good human being.

Aristotle divides the good into three different kinds:

- Of the body (physical: healthy, food, drink)

- External (honor, wealth, status)

- Of the soul (intellect, virtues, knowledge): we need to attend to the soul.

What is the function of human beings? To do so we need to examine the function of all animate beings in nature, including plants, animals, and humans.

All three of them require nutrients for survival; animals and humans are both conscious in a way that plants might not be. Humans are distinct from both animals and plants in that we are rational animals, according to Aristotle.

Because we are rational animals, it follows that our function as human beings is to act rationally; i.e., to live in accordance with reason.

As we said Aristotle links the good of something to its underlying function. We still need to figure out what would constitute good character traits, and what constitutes living in accordance with reason.

Virtues lie in the middle between two extremes: excesses and deficiencies. Living in accordance with reason means adopting a balanced approach. It’s the continuous pursuit of the mean between these two extremes. Our function, to live in accordance with reason, would be fulfilled when we seek the mean and incorporate it into our mode of action. Since this is an ongoing quest that concerns itself with acquiring excellent traits and honing our character, as a result, we need to cultivate the habit of pursuing the mean. This equally applies to our feelings and actions. The goal is to determine the appropriate kind of feeling or act moderately depending on the situation.

For Aristotle, virtues are common to society, and they are ‘universal’ insofar as they apply to the entire community, but acquiring them is relative, conditioned on the situation, the individual, and other factors. A moderate diet for an athlete is much different from that of a non-athlete.

While many moderate actions fall in between two extremes, for example, courage is the middle ground between foolhardiness and cowardice, some extremes don’t have an average, like murder, which is defined as taking an innocent life against its will (and not in self-defense or in battle) is automatically considered a vice that has no mean.

When it is hard to determine where the mean lies on the spectrum of actions, all we need to do is go in the opposite direction of whatever our appetites desire. As such, if I naturally desire to sit down and do nothing all day long every day, doing things in moderation would mean going against my desire in the opposite direction until I find a middle ground between ‘workaholism’ and being a couch potato.

In certain instances, we might find ourselves faced with a choice between one more virtuous action, in other cases what we think might be a virtuous action but on the whole, we might be carrying a vicious action. E.g. ‘courageous’ thieves.

Intellectual vs. Practical Virtues

Aristotle distinguishes between practical and intellectual virtues.

- Practical virtues: habituating ourselves to do what is virtuous.

- Intellectual virtues: seeking theoretical knowledge.

As such, while knowledge is important but is not sufficient. Their relationship is reciprocal. We need to engage in both in order to approximate ourselves to the acquisition of virtue. Being virtuous means that we ought to habituate ourselves to seek the mean, and to become disposed to always do the ‘right’ thing. But ultimately, a life of intellectual contemplation, coupled with practical virtues would put one on the right path to becoming a magnanimous person. To know more about that, you can read more at the following link.

If this has been helpful for you, and you’d like to keep up to date with future articles, you can follow me @decafquest.