We talk about gut feeling, the unconscious, the visceral reaction we have towards certain things, people, events. It is almost never easy to explain what we are feeling in these moments.

Yet we know we are right. We strive to justify it. To find reasons that would back up the conclusions we arrived at, but without any success. Those around us might think we have lost our minds. But oftentimes, we end up being right.

If you’ve had a similar experience before, then it will be easier to relate to what I’m trying to capture in this brief post.

Where does this feeling come from? It sometimes feels like there’s an unconscious side of us that’s rebelling against our intentional, well-thought decisions and plans that we meticulously craft and layout for ourselves.

Sometimes we even spend months and years building a certain habit, a routine, a lifestyle that we think defines us.

Then, overnight, an existential crisis hits us. And everything comes crumbling down like a house of cards.

This crisis doesn’t even have to be triggered by a big event like a pandemic or war, although it could.

It can also be caused by the most mundane event of all, something you hear at work, someone you cross paths with on the metro or down the street, a book you read, or a movie you watch.

Slowly, an internal rebellion begins to spread across us. It starts small, and gradually builds up. We see hints here and there. Then one day something happens, a simple incident changes everything.

It’s almost like an existential event horizon.

You decide to make a leap of faith and change paths, pursue new avenues, cut ties with people you know, and embark on a new journey.

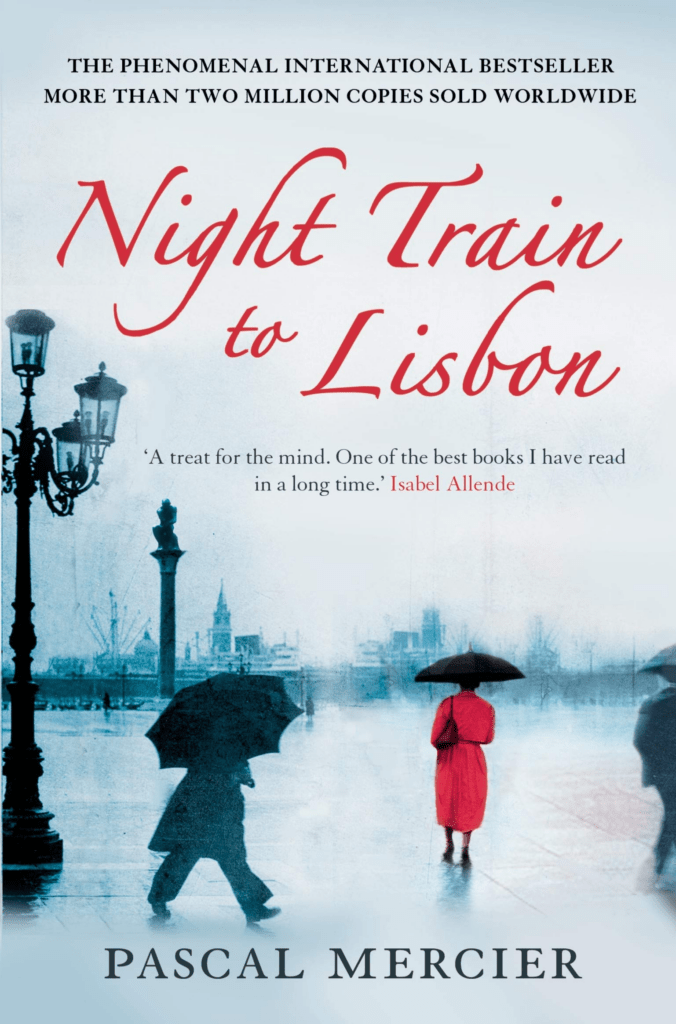

This is where Night Train to Lisbon begins. An existential event horizon drives Raimund Gregorius to leave everything behind and to embark on a quest.

I always return to this novel because it beautifully captures this moment of no return. It touches on the existential undercurrents of experience. These are often difficult to articulate, yet deeply familiar to us all.

I’ll only draw a sketch.

Gregorius is a man of habit. He teaches Greek and Latin at a Gymnasium in Bern. To get there, he crosses a bridge daily. His days are like a Swiss clock. Every day looks the same.

Until one morning he meets a mysterious woman standing on the bridge, reading a letter. He worries for her, but instead of jumping, she turns to him and writes a number on his forehead.

The day is disrupted.

She walks with him for a while, then follows him into the school. He enters the class late — pretty unusual for him. Allows her to sit in the back. The students notice something is off. She walks out after a few minutes.

Later that morning, unable to focus, Gregorius feels an overwhelming urge to leave. He walks out of the school, abandoning his class, his books, and his old life.

He goes to a hotel’s cafeteria. Leaves. Enters a bookshop. Stumbles upon a book by Amadeu de Prado, a Portuguese doctor. Captivated by Prado’s words, he becomes obsessed. The book plants the seed of his journey.

Soon after, he takes a night train to Lisbon on a quest to track down the author of the book, but deep down, it’s a quest to track himself down… the self he lost along the way when he became all too ossified by a daily routine conditioned by external circumstances, duties and obligations, failing to experience anything new or step out of his comfort zone.

Somewhere deep within us, we might recognize this moment.

The existential event horizon.

Two quotes from the novel:

Furious Lonliness

Is it so that everything we do is done out of fear of loneliness? Is that why we renounce all the things we will regret at the end of life? Is that why we so seldom say what we think? Why else do we hold on to all these broken marriages, false friendships, boring birthday parties? What would happen if we refused all that, put an end to the skulking blackmail and stood on our own? If we let our enslaved wishes and the fury at our enslavement rise high as a fountain? For the feared loneliness – what does it really consist of? Of the silence of absent reproaches? Of not needing to creep through the minefield of marital lies and friendly half-truths while holding our breath? Of the freedom not to have anybody across from us at meals? Of the fullness of time that yawns when the barrage of appointments falls silent? Aren’t those wonderful things? A heavenly situation? So why the fear of it? Is it ultimately a fear that exists only because we haven’t thought through its object? A fear we have been talked into by thoughtless parents, teachers and priests? And why are we so sure the others wouldn’t envy us if they saw how great our freedom has become? And that they didn’t seek our company as a result?

Silent Nobility

It is a mistake to believe that the decisive moments of a life when its direction changes for ever must be marked by sentimental loud and shrill dramatics, manifested by violent inner surges. This is a sentimental fairy tale invented by drunken journalists, flashbulb happy film-makers and readers of the tabloids. In truth, the dramatic moments of a life-determining experience are often unbelievably low-key. It has so little in common with the bang, the flash, or the volcanic eruption that, at the moment it happens, the experience is often not even noticed. When it unfolds its revolutionary effect, and ensures that a life is revealed in a brand-new light, with a brand-new melody, it does that silently and in this wonderful silence resides its special nobility.